One of my favorite stand-up comedians, George Carlin, the gods rest his soul, did a bit in the early 70s’ about seven filthy words you couldn’t use on public radio or televison. That list hasn’t changed much. I was recently strongly reminded in one of my workshops that there are also certain “dirty” words that still rattle people when found in poetry. Unnecessarily vulgar was the launched refrain: why can’t a poet get the same message across without being so crude? Of course, I tried, facing resistance, to raise a few obvious questions. Vulgar to whom? Indeed, assuming you have an adult audience, why (or why not?) use crude and uncensored language? Are we again talking about finding our own authentic and unique voice, while also seeing the value in the voices of others, even if they do happen to disturb us? Are we once again trying to define poetry and what makes a poet? What exactly are we up to in the room?

Our group discussion began after viewing a few video clips, the last of a spoken word artist, Thea Moynee, on a Def Poetry Jam HBO special. She ellicited the most commentary, mostly negative, after presenting a piece called “Woman to Woman.” In it, she discovers her man cheating and addresses the other woman in no uncertain terms. I saw a performance artist using and owning her body, language, message, and not hiding any daggers within clever metaphors or coded pretty phrases. Moynee seemed spot on, given the volatile occasion. They saw someone deliberately trying to shock and not being herself; they saw a person using inauthentic language that was disturbing and vulgar. I had to review the DVD later to see exactly how rude she was. On second viewing, she seemed even more real and credible to me, and I didn’t hear any phrase more horrible than… Yes, there is a difference between Spoken Word and “POETRY.” In the end, what one considers to be poetry depends on personal tastes that are based on one’s knowledge and, dare I say, ideologies.

It’s important to note: this group consists of mostly white retired seniors and not a diverse mix of twenty-something English majors. Only recently have they begun to cover more of the poetry landscape and move beyond light rhyming verse in their own writing. And I did provocatively set them up a little by presenting film clips of a few white (most are) sedate (most are) mavens from the Academy of American Poets, followed by a Chinese and then a black spoken word artist that were dramatically animated (most are). And even if it complicates matters, I should mention race at this point. Not doing so would be disingenuous and cowardly of me.

In the foreground is the seventy year-old white woman (just visiting for the day) who said she had been remarkably impressed with a black poet who, she said, spoke so beautifully that it made her think differently. How would you repsond to this statement?

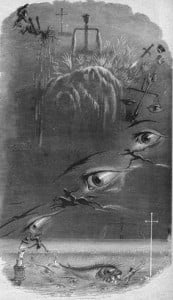

The following week the only African-American in the group, a retired social worker, who was more sympathetic towards Thea Moynee, yet, not completely happy with her diction either, brought in a poem by Helene Johnson, an underappreciated Harlem Renaissance poet, to show that poetry dealing with sexual situations could be handled (by a black poet?) with more decorum. The speaker, a widow, in Johnson’s poem seductively addresses a potential lover after first turning him away out of guilt. I found the poem intriguing; and this group member raises some interesting issues with this poem. For example: true, Moynee and Johnson are both black women and their poems have something to do with sex and infidelity; but they are different people and present different situations in their poems. Johnson was known for being unusually shy and was not a widow when she wrote this phantasmogorical piece; she also published her last poem in 1937. Moynee, on the other hand, performed her poem at Harlem’s Apollo in 2004, and I would wager she based her performance on personal experience with infidelity; even if she didn’t, most us know of women, if only on a screen, who have caught the other woman and let her have it using language far more raw and far less creatively. And it’s not a revelation that African American women publishing before and after the depression have known how to handle strong subjects with conservative language that is suitable for popular consumption. Looks like we have the start of an interesting dialogue if group members want to pursue it. As usual, I’m left positing more questions than producing explanations.

Who are you writing for? What is going into your decisions to use certain words over others? How much do you censor your work? Why? What would you choose to write about if you were totally free to do so? Sadly, some poets internalize such severe oppressive censors that they can never fully and authentically explore themselves and then express what they find creatively. Repression is alive and strong in the U.S; I’m confronting it now, right here, on this blog; I’m working like all poets and writers, with internal and external censors and considering known and unknown consequences for my choices. I still haven’t heard what group members think about their occasional appearances on this blog, even if anonymously; I’ve asked them to read it and still no feedback. What corrections, additions, deletions, if any, would some want to see in my account so far?

I did find Johnson’s poem stimulating. See it below followed by my poem in response.

Widow with a Moral Obligation

Won’t you come again, my friend?

I’ll not be so shy.

I shall have a candle lit

to light you by.

I shall my hair unbound,

my gown undone,

and we shall have a night of love

and death in one.

I was very foolish

to have run away before,

but you see I thought I heard

him knocking at the door.

But you see I thought I saw

him smiling in your smile,

and I saw his lips call

me something very vile.

It must have been my conscience

or a quirk in my head,

for I knew he’d been

a long time dead.

We buried him one morning

in the sweet cool rain,

but when you come tonight,

we must bury him again.

You must come and rid me

of my dear leal wraith.

We can bury him so easy

when he’s lost his faith.

Stab with little poiniards—

every kiss will be a knife.

And we will be cruel

for life is life.

Ah, come again, my friend,

I’ll not be so shy.

I shall have a candle lit

to light you by.

I shall have my hair unbound,

my gown undone,

and we shall have a night of love

and death in one.

Dead Husband With a Moral Obligation

How can you speak about a moral obligation

then plot my second death so you can fuck?

Should I sacrifice myself for your liberation?

Say it: the day you two buried me, you saw luck

in the rain you felt like labeling “sweet and cool,”

since your veil for absent tears. I now wonder:

when did I become a “him,” a nameless fool

easily destroyed if you simply fuck another?

Is my name coming back to you? I swore on it

when we married. Think, my love: I hold a faith

you or our fucking friend can only counterfeit.

I am not who you imagine: this honest wraith

can stand—or sit—to see you fucked; a voyeur

I never was; but now I will be, for spite. Go light

a candle to better see your twisted carnal lure;

unbound your hair; undo your gown; take flight;

but know this: when you least expect a knock

at the door, or to see my smile in his, or his lips

form the vilest names, I will bring it all. A rock

breaking through a bedroom window as his hips

dig between your thighs on that last doggy thrust, would

be a nice touch, if I happen to be in the neighborhood.

Perhaps it’s a good time to revisit the DVDs of Ginsberg and Howl. I have Bukowski waiting in the wings.

Until next time,

keep writing.

Peace,

Andrés Castro